The chapters by Willetts and Goldman in Diversity in Disney Films discuss racism. The opening of Willetts’ chapter says begins: “[t]here is little doubt that for the young and young at heart, Disney is synonymous with magic and fantasy, a wish factory if you will. It is an alternate universe that operates at the pleasure of young children, centering their world view, creating a place where animals speak, one never grows old and the possibility of becoming a prince or princess seems far more attainable than becoming a scientist or teacher” (9). Of course, the rest of the chapter is dedicated to emphasizing that this wish factory is for only certain children — white (middle and upper class) children. Also discouraging is that which goes unanalyzed: the idea that it is easier to become a princess than a scientist.

Willetts goes on to describe how Disney portrays its racism — often characterizing African Americans as primate-like creatures, such as through statements such as: “[i]rrespective of the manner of portrayal the intent was the same: to illustrate the differences between the races, thereby validating the notion of Africana people as direct descendants of ‘the missing link,’ more closely related to primates in ancestry, appearance and behavior than humans (Europeans)” (10). Depictions often set black and white characters into opposing depictions — whites were “good, pretty, [and] intellectual” while black people were “bad, ugly, [and] emotional.”

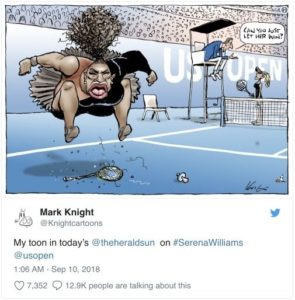

Above, is my chosen media for the week. I chose it because it directly engages the concepts of the readings for the week. This cartoon is from September 10. It is a cartoon drawn by an Australian artist, depicting Serena Williams’ breakdown at the US Open. This cartoon immediately went viral and the artist’s response was that it had nothing to do with race or gender; yet, anyone looking at it can obviously see the cartoon is very much about both. It particularly deals with the concepts Willetts addresses in “Cannibals and Coons: Blackness in the Early Days of Walt Disney.” Serena’s features are featured exactly in the terms specified in the chapter. She is depicted as “bad, ugly, emotional, [and] savage” (11). Her features in the cartoon make her appear more ape-like than human. The cartoonist exaggerates her features, making her appear more masculine than feminine. She is drawn ugly. Her behavior in the cartoon is coded as bad, emotional, and savage. In the cartoon, she is having a full-blown tantrum; whereby she’s jumping up and down into the air while screaming after breaking her racquet. While her white opponent is drawn to appear like an actual human being and in complete opposition to how Serena is drawn. She’s thin, blonde, and has appropriately drawn features. Her opponent is standing still, calmly speaking to the line judge.

Goldman’s chapter on Disney’s “Good Neighbor” films discusses how these films were produced in order to bridge international relations. However, in reality they followed and further forwarded stereotypes of Latin America that continue on into contemporary animation.

Sammond’s chapter on race in animation talks about the white-black racism in early cartoon shorts. The most interesting exploration in the chapter are the bits involving minstrel characters, the most well known and most talked about example being Mickey Mouse.

Finally, Turner’s chapter “Blackness, Bayous and Gumbo: Encoding and Decoding Race in a Colorblind World” uses Stuart Hall’s work to discuss the opposing readings of The Princess and the Frog. In her chapter, Turner explains that the film was the first to feature black characters since the extremely controversial Song of the South. The article ends by saying that The Princess and the Frog was in a situation where it couldn’t win. That is, “[f]or some it will be too Black, for others not Black enough” (94). I tend to wonder if it would have been placed in this can’t win situation if Disney had incorporated more diverse characters throughout its history of films.